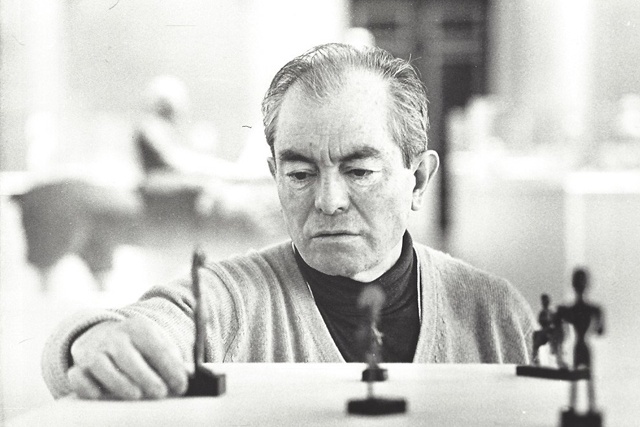

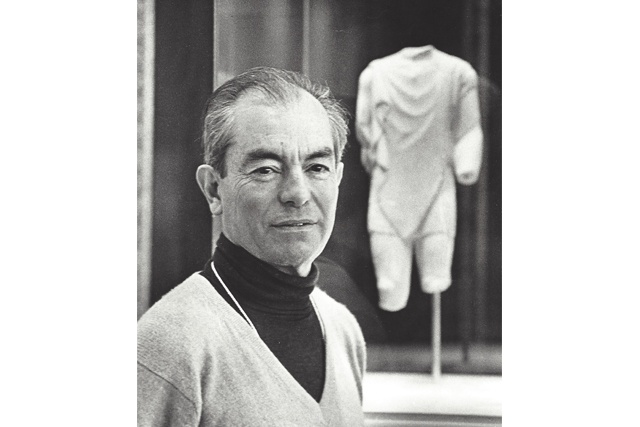

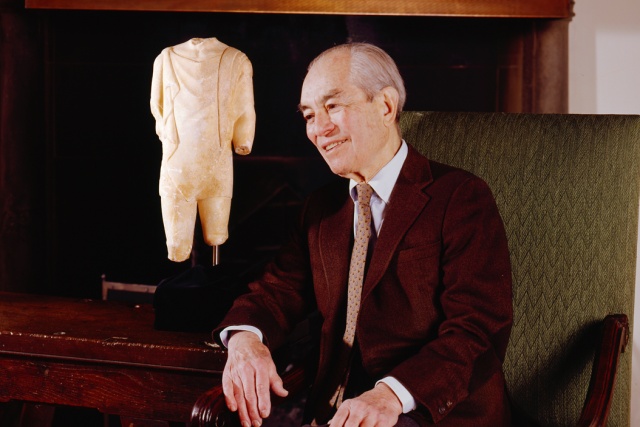

Son of the Bolivian ambassador to France, George Ortiz grew up in Paris, was schooled in the UK and US, then briefly read philosophy at Harvard before embarking on a journey to Greece that changed his life. He started collecting in 1944 and over many years of dedicated collecting created one of the most important collections of ancient art still in private hands.

How and when did you start?

It all goes back to my adolescence. I lost my religious faith, studied philosophy and became a Marxist. I was looking for God, for the truth and for the absolute.

In 1949 I went to Greece and I found my answer.

The light was the light of truth and the scale of everything was on the scale of man. And Greek art exuded a spirit which I was much later to perceive as what I believe to be the spiritual birth of man in the same fashion that this physical birth took place in East Africa some two million years ago.

What is that spiritual birth?

It is the awareness that man is the centre of things and that the elements or the gods must be placed in their right contexts. A new anthropocentric but not ethnocentric approach that achieved fulfilment in Athens, in the 5th-4th century B.C.

It is a humanism wherein the rational mind helped by observation, pragmatism and logic has the potential to seek everything there is to learn about man and the cosmos.

It is a search after the truth and the universal principles in each man, leading to universal concepts, guided throughout by a moral approach. It is the need perpetually to call into question oneself, one’s beliefs, one’s attitudes, one’s stance, one’s image of oneself and others. For as Polonius says in « Hamlet » :

« This above all – to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man. »

(I, III, 78-80)

It is the realization that man is a political animal, and the choice of democracy as the most appropriate system within which there is absolute political equality for all, embodying discussion and debate and the right for each to express himself. Each citizen protected by the sacred inviolability of the law.

It should ensue that each man assumes his full dignity and responsibility in freedom within an ethical context propitious to the fulfilment of his potential, each contributing thus to the evolution of humanity.

The acceptance of this spiritual birth should enable all men to understand and to relate to each other, the above concepts being the same for all, regardless of race, religions or mores.

Already in Greece, in late Summer 1949, I realized that the answer to all my problems and anguish was to be found within myself. It was no fault of others, of systems or circumstances. It was within myself that lay all the answers.

I soon gave up my Marxism, realizing that its implementation, the putting into practice a theory in contradiction with human nature, could only become a depraved deformation of an utopia – however beautifully moving and appealing the « from each according to his ability, to each according to his need » (K. Marx and F. Engels, Complete Works, vol. 19, p. 20).

Back in Paris in the Autumn of 1949, I went to see a dealer who had a « Cycladic » forehead and whom I had met in the Herakleion Museum and said : « I want to collect Greek art, will you help me? »

And that is how I started. Possibly I instinctively hoped that by acquiring ancient Greek objects I would acquire the spirit behind them, that I would be imbued with their essence.

I had no knowledge; I had never studied archaeology; and I did not go to museums.

My approach was purely intuitive, instinctive. The vision of certain objects struck me viscerally, then they came to fascinate and move me, I let them speak to me, I let their content and spirit nourish me. I began to go to museums and looked with intensity. I learnt by looking, by feeling, and then reading the labels and comparing. Why, what, when?

One of my earliest acquisitions was the Neolithic idol, no. 42. She moved me when I first saw her, and amazingly when I looked at her in moments of anguish or doubt these disappeared. I wondered why. In her time she was an idol of fertility, a protection against the fates, fire, flood and drought. She was a promise of plenty and the continuation of the race.

What is it in this idol that alleviated the anguish of Neolithic man and mine though of an apparently different nature?

I once read that in Africa certain immensely fat women are held in the highest esteem, for in time of famine, they survive longer thanks to their fat. Was not mine also an existential anguish? Thus the idol’s steatopygous forms are not only physical but contain a spirit, the answer to man’s most primeval needs, still a part of all of us, however deeply buried.

The miracle of Greek art is to have succeeded in expressing the maximum of perfection with and within an acceptance of man’s finiteness and scale.

Art is a projection of the ego, an urge for survival, a need for beauty and the absolute. After all, is it not a material manifestation of man’s noblest feelings, a surpassing of oneself? An expression of an idealism, visionary but harmless, essential to his existence and survival. This is neither the case with religions nor ideologies often responsible for extensive crimes against humanity and untold millions of deaths.

Little by little over the past forty-three years, the collection has grown more and more into a coherent whole. Objects came my way, and some of them unquestionably because they had to do so. It is as though, imbued with the spirit of their creator, they came to me because they knew I would love them, understand them, would give them back their identity and supply them with a context in keeping with their essence, relating them to their likes. But this is no place to go into detailed stories of certain precise examples that would prove this.

The most recent example was Prince Siddhartha, no. 173. A surprising series of circumstances led me to the awareness of his existence and, notwithstanding all manner of pressures on me, he joined the collection. This may seem surprising, as Gandharan art does not particularly attract me. But he is of a dimension that surpasses all contingencies, an overpoweringly strong presence. He is a very handsome prince, the son of reigning monarchs, he has a beautiful young wife and a little son whom he adores, all the trappings of wealth and power, and he is adulated by his future subjects. But one morning he wakes up, abandons all and goes forth into the world in the pursuit of truth. He is the future Buddha.

The collection has become almost as though a living entity which I have to go on looking after. Today its main body is Greek art from the Neolithic to the Byzantine with many of the peripheral cultures, preceded however by a few examples from the greatest civilizations that came before the Greeks, and born on great rivers: Sumer in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and the Euphrates, Egypt with its main artery the Nile, and China with the Yangtze and Yellow River, represented here by one example only, no. 209.

As an early Greek philosopher observed, everything is in flux and man is perpetually in evolution. Thus it is important to realize that, whatever the miracle of this spiritual birth, Greek civilization was enormously indebted to the Near East and Egypt. There started the first sedentary settlements that became in time cities with their religious and political hierarchies, leading to the invention of writing, mathematics, astronomy, etc. What changes is the assessment of facts, a new perspective, a heretofore unknown awareness, a humanism which reached its maturity in 5th century Athens in the plastic and dramatic arts and in some other centres of the Greek world at that time. This humanism is foreshadowed in the Neolithic art of Greece. For example the seated terracotta idol, no. 44, with the tenderness expressed in the pose of the forearms and the hands on the right knee, some five thousand years earlier. In no other Neolithic art that I have looked at do I perceive such feelings.

Certain cultures and civilizations of the past have admirably portrayed different animals, but none with the personal and human touch of the Greeks who loved them so much, harmonizing with their images and making some of them as though they were almost human: man become animal, in a Platonic sense, conveying the characteristic of their essence. Some of them exude spontaneity, vitality and humour, not to mention a sensitivity of feeling.

For example the Geometric mare, no. 76, expressing maternal love as she tilts her head towards the foal which she is about to suckle, and which is now missing. Also, the doe, no. 78, as though on the edge of a forest in the mist of early dawn as she quivers with an almost human hesitancy in an awareness of potential danger. Note the spirited mischievousness of the smiling goat, no. 108, of the Archaic period from Greece proper with a human glint in his eye; the playful « dancing » bull, no. 120, from Magna Graecia where it is fun to live, for the land is bountiful.

The Kriophoros, no. 140, from the Greek world stands at this exceptional moment of transition from aristocracy to democracy, from archaic art to classical art, from stylisation to naturalism, in the period called Early Classical or the Severe Style. The ram and his bearer are realized with considerable naturalness, but above all the bend of the animal’s neck with its slight bulging on the underside expresses with infinite tenderness the apprehension of the ram because of his unnatural and somewhat uncomfortable position. Has the artist portrayed the animal’s premonition of the fate that may await him?

The rhyton in the form of a deer’s head, no. 154, was surely executed by a Greek influenced by the « Animal Style » of the Scythians and possibly produced for a Scythian prince. One almost sees and feels the life that permeates the animal’s muzzle with such sensitivity. The same approach is also to be found in the Achaemenid-style rhyton with a buck protome, no. 206, surely Greek workmanship and of an earlier date but from a similar or maybe even the same workshop, produced this time for a Scythian nobleman, a wealthy Greek of the coast of Anatolia or a Persian satrap of the same region. The poise of the head with its one remaining antler conveys a humanistic understanding of an animal’s sensitivity that I find deeply moving and particularly beautiful; it is, if I may use the expression, a dream object.

Pure Achaemenid objects such as the amphora with ibex handles, no. 205, and the rearing ibex, no. 207, whatever their artistic merits, lack the humanism of previously mentioned works of art. The same is true of the admirable onager heads, no. 209, with their quivering liveliness.

Particularly attractive is the so-called « Animal Style », so spirited and imaginative. Note the naturalism of the Scythian stag on tiptoes, no. 214 bis.

In the early Byzantine period permeated with Greek spirit, whose birth is contemporary with the end of the Roman Empire, a new dimension is added. In the head of Gratian (?), no. 246, executed like a cameo, we see the portrait of a young prince, twelve to fourteen years of age, imperious, very spoilt and possibly somewhat cruel. In no. 251 which we think of as the head of the Virgin, we see a juxtaposition between the virginal purity of her lower face with a young girl’s chin and mouth, and the pathos of her sad eyes, full of melancholy and suffering, with the longitudinal creases between the eyebrows. And the portrait of a high official, no. 248, exudes a compassionate understanding and spirituality.

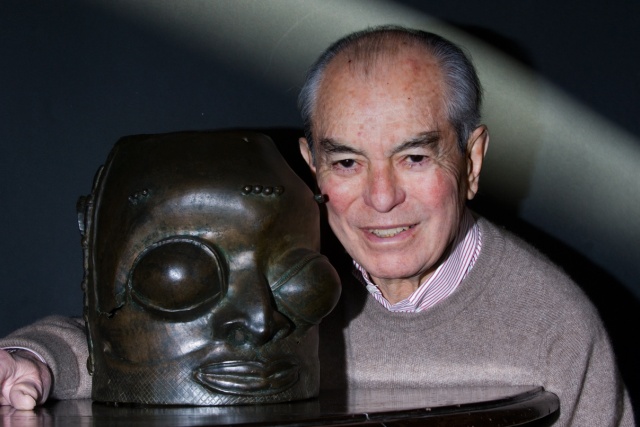

How does ethnography fit this collection? Because some of it is very powerful, very pure or very beautiful sculpture, or both, often with a strong inner content. I have always liked African sculpture when it is genuine, which means unadulterated by European contact. And the Africans as no other peoples have been able to capture and express the savagery of nature in some of their sculptures, for nature is not burdened with considerations of morality or justice, it just is. See for example the Nok head, no. 261, with its powerful psychic content, and « Bulgy eyes », no. 263, with its mystical strength.

Some twenty-five years ago I went to the Pacific and discovered a sky different from that of Greece but equally of a pureness as nowhere else and an ocean with its atolls surrounded with necklaces of white foam as the sea beats against the outlying coral reefs – a breath of fresh air, an escape from the rational and technical materiality of the western world. Notice the purity of forms of the wood stool, no. 269, the basalt pounder, no. 268, the Easter Island paddle, no. 270, the implement, no. 277, and the dagger, no. 276 not to mention the Matty dish, no. 279, of which I once wrote « the most successful form for a dish ever made in any civilisation, of masterful abstract and pure line. The relationship of curve and plane, of solidity and lightness, of strength and elegance to its form creates a volume which is a great sculpture – a sheer delight to the eyes, an homage of man to space.

Might it not be that the timeless quality of life in some primitive societies contributed to their being able to create such perfection?» This timeless quality surely applies also to the Cycladic vase, no. 49.

Feel the savage presence of the Hawaiian sorcery image, no. 278, the might of the Rarotonga figure, no. 274, probably a representation of Tangaroa the Polynesian God of creation and of the sea, with the seat of his « mana » (the concept of prestige and puissance) in his overpowering head, and the purity, simplicity of line and perfection of form of the Nukuoro deity, no. 280.

What has happened to this spiritual birth in the West?

It is responsible for our scientific and medical discoveries implemented by technology, resulting in our high standard of living. The shortcomings are the exaggerated materialism that ensues and the practical difficulties of democracy working with vast populations; the impossibility of paralleling the Athenian Agora where each citizen, humble or high-born, poor or rich, could speak out and be heard, participate, discuss and vote in full understanding.

Today, our populations have little real concern, no time although our material progress results in more free time. In the measure that they are informed it is by the media that forget their sacred responsibility to relate information as objectively as possible. They should express all opinions truthfully, with equanimity, regardless of their personal leanings and, honestly stating their stance, comment freely.

Most of the politicians in the West have forgotten their mission and consider politics a career; their ego projections, self-interest and power more important than their call to serve humanity. They are responsible for not giving the right example and for our failing ethical and educational standards. Materialism has impaired our courage, but it is not materialism that is at fault. It is the escape into materialism, it is a refusal of most men to develop their potential and assume their responsibility.

What has happened to this spiritual message in the rest of the world?

It has not been understood or seen as what it is. It has been assessed as somewhat distorted by Judaeo-Christian religions and associated with western white man. It has been equated with our racism and our past politics of colonialism and imperialism, with the dogmatism of our religions, with our distortion of the use of reason giving birth to ideologies which have been responsible for millions of deaths and immense suffering.

The rest of the world is in the process of aping, copying and enlarging upon the science and technology that flowed from this spiritual birth, but simultaneously rejecting the most important aspects of this birth for reasons I have suggested above.

It is, I am convinced, the spiritual birth of all humanity, and it is only because it took place geographically where it did, that the West has been lucky enough to benefit from it.

There is a certain hope in certain peoples wishing to adopt the political system of democracy.

Humanity will not survive unless all men can relate to each other, unless all men can develop a humanistic and ethical approach to life and to each other. The difficulty for all is the balance between elites and the masses, the masses’ understanding and elites’ giving of themselves, in the hope that each man will assume his dignity in a responsible way.

The other difficulty is that, superior animals that we are, we tend to find ourselves distorted by the material creations of our intelligence which enable possession, accumulation and power. A precarious balance can surely be maintained within the political system of democracy, the rule of law, the division of powers between the legislative, the executive and the judiciary, and the awareness of each that if his role and participation in the « res publica » is not ethically conditioned and imbued with humanism, there will be no long-term survival.

The collection you will see is a message of hope, a proof that the past is in all of us and we will be in all that comes after us. Let these works of art speak to you, hopefully some of them will move you by their beauty and reconcile you to your fellow men however different their religions, customs, races or colour.

For these works of art are the product of humanity.

George Ortiz - 2004